(The English-language edition of Peig published in 1974 kept the word cúl, presumably to avoid printing its risqué translation.)Īfter primary school Peig went to live and work with Nell and Séamas Curran, who owned a shop in Dingle. She recalls how her heart jumped for joy when she heard her brother Pádraig was visiting one day when he arrived “I ran to meet him he took me up in his arms and kissed me lovingly.” Her sister even says of Peig’s mother’s love for her: “The dear woman thinks it’s out of your cúl the sun rises.” Cúl, in this context, means behind, or backside. One of the book’s key themes is the love between Sayers and her family.

#Footsteps of peig sayers full

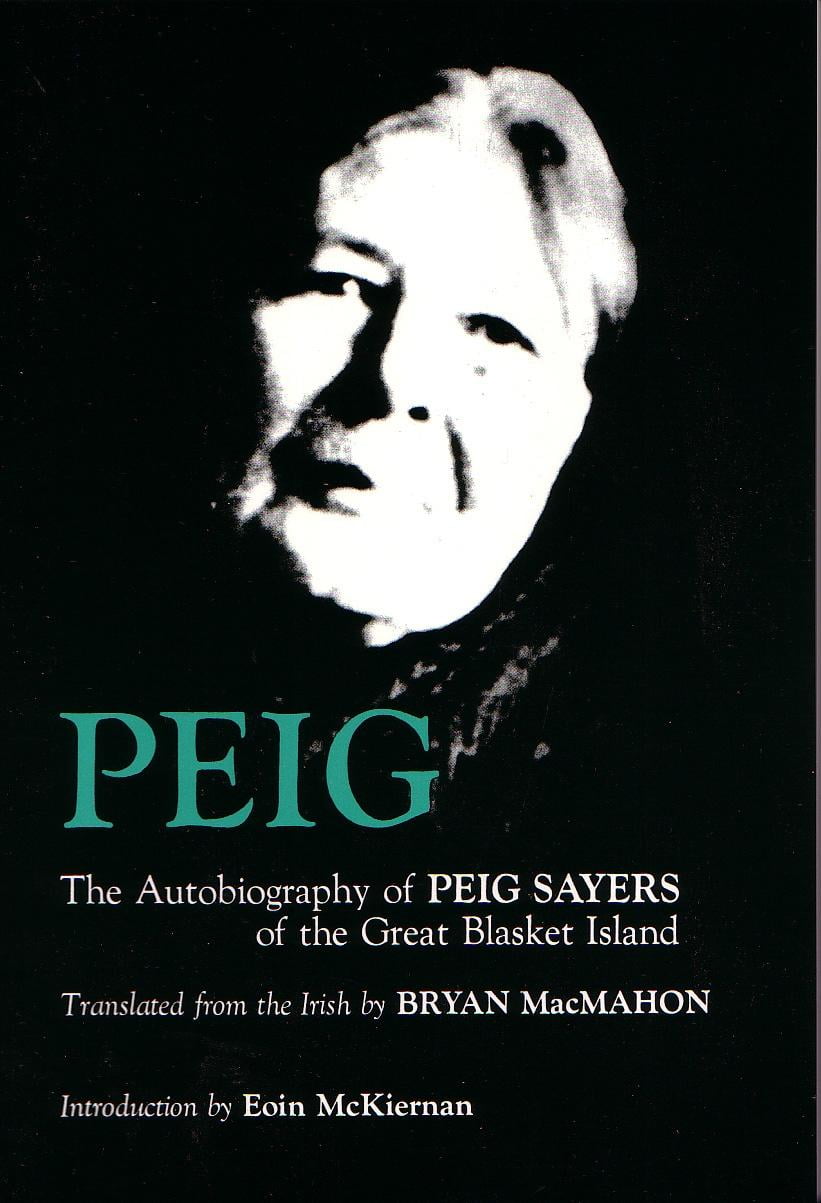

Photograph: Keystone-France via GettyĬontrary to popular belief, the book is full of attention-grabbing, exciting and even funny stories. Vanished way of life: farmers in Co Kerry in the early 1900s. While we think of Sayers as an old woman sitting at the fireside, most of Peig is about her life up to the age of 23: her early days in Dún Chaoin, her time living with a family in Dingle from the age of 12, a period she spent working at a farmhouse outside the town, her marriage and move to the Blasket Islands at the age of 19, and the birth of her first son. And even though Sayers’s memoir is about a vanished way of life in rural Co Kerry at the tail end of the 1800s, Silas Marner is about a linen weaver who lived in a northern English slum in the early 19th century, and Macbeth – a play written 400 years ago, in Elizabethan English – is about an 11th-century Scottish king. Yes, the poverty it depicts is a tragedy – but so is the domestic violence of Purple Hibiscus, the organ harvesting of Never Let Me Go and the Nazi occupation of All the Light We Cannot See, all of which are currently on the Leaving Cert syllabus. The familiar claim is that Peig is such a depressing, unrelatable story of hardship and woe, in which Sayers complains from start to finish about her terrible misfortune, that it puts school students off speaking the language for life. Since Colm Bairéad’s film An Cailín Ciúin was nominated for this year’s Oscars, the newspaper is just one of the US media outlets that have published articles about the Irish language – including, inevitably, her infamous autobiography. Or to be more precise, in the Los Angeles Times.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)